Combining numbers and text into strings: f-strings#

We frequently need to combine numbers and text: legends and titles on plots, formatting the output from a model that summarizes the findings in a human-readable manner, etc. If we have a variable, let’s say, number_of_apples and number_of_pears and we want to print out a sentence that says how many apples and pears we have, we need a way to combine a string and a number to say something like “I have 42 apples and 24 pears”. There are a few approaches to doing this programmatically.

Our first thought may be to use the + operator, knowing that it can concatenate strings together and convert any numbers to strings along the way. For example, for our apples and pears example, we may approach that as follows:

number_of_apples = 42

number_of_pears = 24

our_string = "I have " + str(number_of_apples) + " apples and " + str(number_of_pears) + " pears"

our_string

'I have 42 apples and 24 pears'

Using all of these plusses and separated strings can get very messy. There’s a much simpler way to do this with format strings and f-strings. Format strings apply the format method to a string and replaces the blanks in the string (defined with brackets {}) with the corresponding argument to the format method. Let’s demonstrate this by repeating the above example using a format string:

our_string = "I have {} apples and {} pears".format(number_of_apples, number_of_pears)

our_string

'I have 42 apples and 24 pears'

This is nice since it automatically converts the numbers to strings without the need for the str() function. While you may see this format method from time-to-time, the preferred way of doing this now is through f-strings, which are the easiest of all to use. With f-strings, you simple append the letter f before your string and fill in the brackets with the variable you want inserted - very simple. Let’s redo the above example with f-strings:

our_string = f"I have {number_of_apples} apples and {number_of_pears} pears"

our_string

'I have 42 apples and 24 pears'

You’re not limited to putting in integers into the string, here’s an example mixing different types of data into one string:

name = 'Arwen'

age = 28

favorite_fraction = 1/3

our_string = f'My name is {name}, I am {age} years old, and my favorite fraction is {favorite_fraction}'

our_string

'My name is Arwen, I am 28 years old, and my favorite fraction is 0.3333333333333333'

We were able to easily mix data types and combine them in a string. However, we can see that the fraction shows a lot of digits: far more than is necessary. This brings us to another feature of these strings: our ability to control the formatting of the output including the precision of the number of digits. To do this, we can add add a colon : after our variable with a number formatting code. For example, let’s say we only wanted 2 digits after the decimal. We could tell the f-string to do so with the .3f code which says to use 3 points after the decimal and represent it as a floating point number. Let’s see that in action:

our_string = f'My name is {name}, I am {age} years old, and my favorite fraction is {favorite_fraction:.3f}'

our_string

'My name is Arwen, I am 28 years old, and my favorite fraction is 0.333'

Perhaps we want to be extremely precise with age and include 2 decimal places. We can use the same approach and use the fomatting code: :.2f as shown:

our_string = f'My name is {name}, I am {age:.2f} years old, and my favorite fraction is {favorite_fraction:.3f}'

our_string

'My name is Arwen, I am 28.00 years old, and my favorite fraction is 0.333'

We could even add in a newline character \n. This \n character is known as an escaped character, which, when printed, breaks the string content into a two lines as shown in the example below:

our_string = f'My name is {name}, I am {age:.2f} years old,\nand my favorite fraction is {favorite_fraction:.3f}'

print(our_string)

My name is Arwen, I am 28.00 years old,

and my favorite fraction is 0.333

Sometimes we want to specify the width of our string. Let’s say we were printing numbers as we counted from 1 to 20. We could easily do this with a f-string as follows:

for i in range(20):

print(f'{i+1}')

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

Since it’s a decimal integer instead of a floating point integer, we can use the :d format string to indicate that (the output will be the same in this case, but it specifies how to represent the string):

for i in range(20):

print(f'{i+1:d}')

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

However, what if we wanted the numbers all be the same width REGARDLESS of whether they had one digit or two? In that case, we can fix the WIDTH of the string by specifying how many digits should be included. Let’s say we wanted 3 digits (so this could count up to 100 and remain right-justified):

for i in range(20):

print(f'{i+1:3d}')

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

This becomes even more obvious if we replace the empty spaces that the come before the numbers with zeros. To do so, we just change our format string from :3d to :03d and voila:

for i in range(20):

print(f'{i:03d}')

000

001

002

003

004

005

006

007

008

009

010

011

012

013

014

015

016

017

018

019

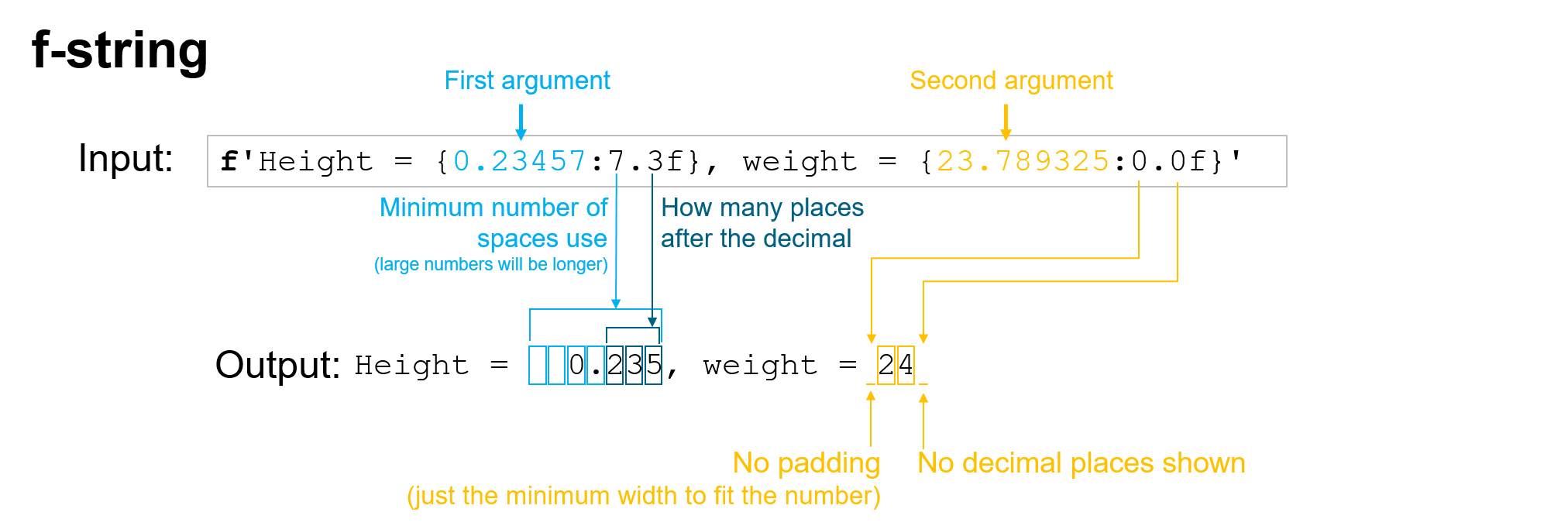

To summarize, here is a figure that captures some of the key topics we discussed with respect to f-strings and then compares it to the equivalent for format strings to see side-by-side the differences. As a rule: USE F-STRINGS INSTEAD OF FORMAT STRINGS! They’re easier to code, easier to read, and are the preferred approach to string formatting.

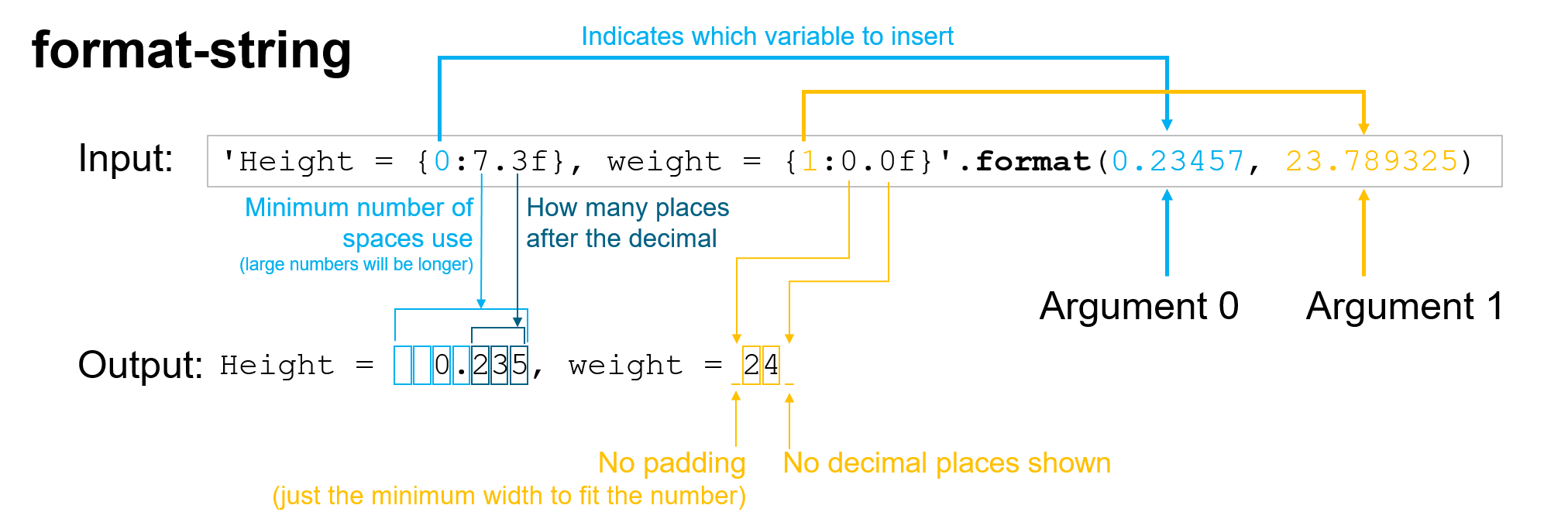

And for comparison when you encounter it, format strings:

Recap#

f-strings and format strings are ways of combining variables of different types (most commonly integers, floating point numbers, and strings) into a single string

These tools are commonly used for creating figure titles and legends, command-line output, and for summarizing data in a human-readable way

We recommend that you use f-strings for their convenience of use, legibility, and current adoption by the wider community