Variables are pointers to objects#

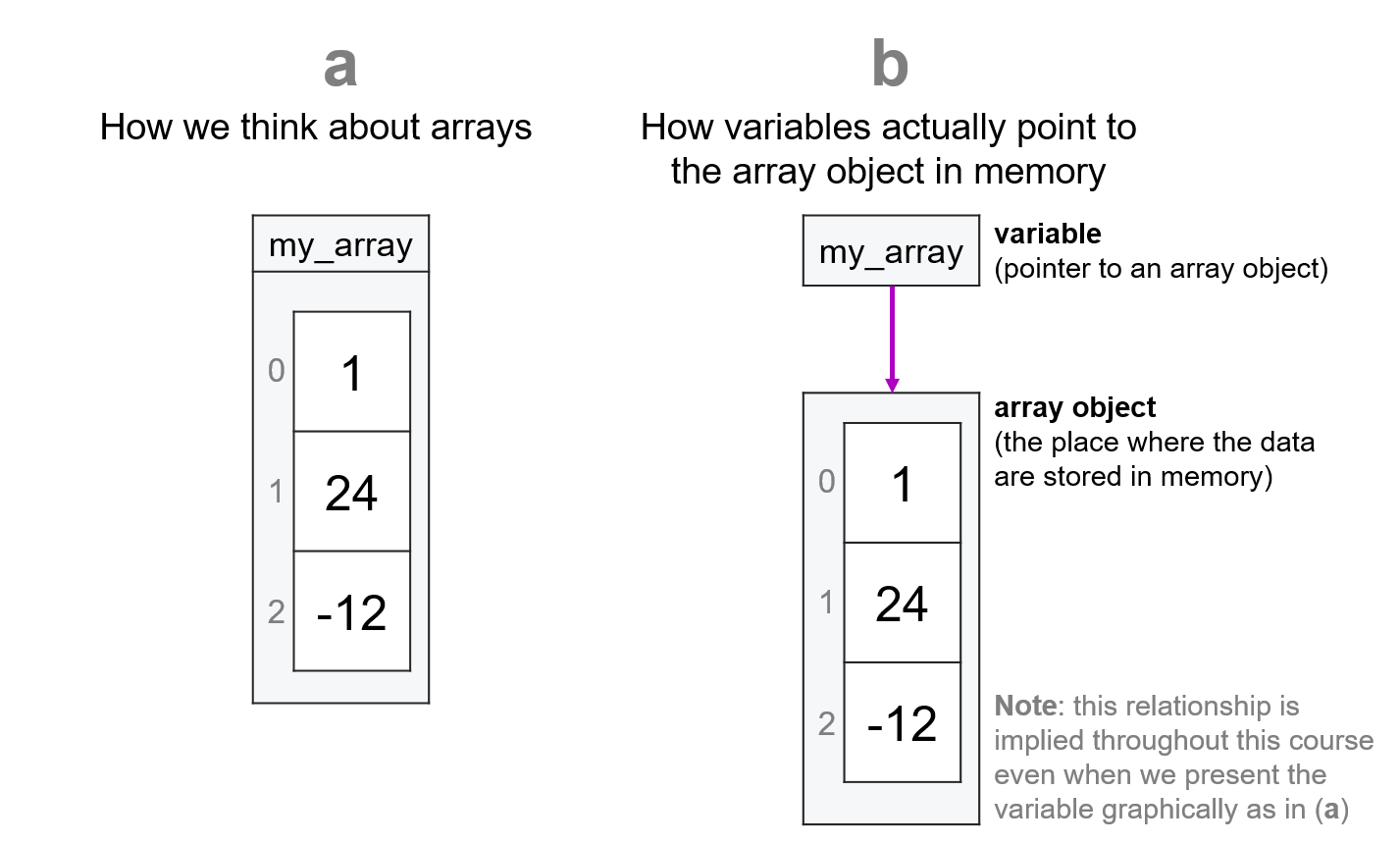

Up to this point, we’ve been representing arrays in Python as shown in the figure below under “a” - suggesting that the variables ARE the objects they point to, shown here in terms of the relationship between my_list and the contents of the corresponding array.

In Python, variables and the objects they point to live in two different places on your computer. As a result, in Python, it’s best to think of variables as pointing to the objects they’re associated with, rather than being those objects. Personally, I’ve always liked the analogy of your computer being a big warehouse, where variables are just the entries in the inventory book used by the warehouse manager: the variable tells you how to find the thing you want, but it is not the thing itself. This is true of lists, numpy arrays, integers, or strings. The name we give it is the variable, and it is a pointer to the place in memory that contains the actual data.

So when you create a new array, Python puts that list somewhere in memory, kind of like how you might put something big on a shelf in a warehouse. The variable associated with that list (say, my_array) actually just stores the location of the shelf where that list was placed (which we call a reference or a pointer). This is represented in the figure below in “b”.

Whenever we show arrays, we’re taking som liberties by representing them as shown in a to make the figures a bit simpler / more concise. In reality, what’s always going on is what’s shown in b.

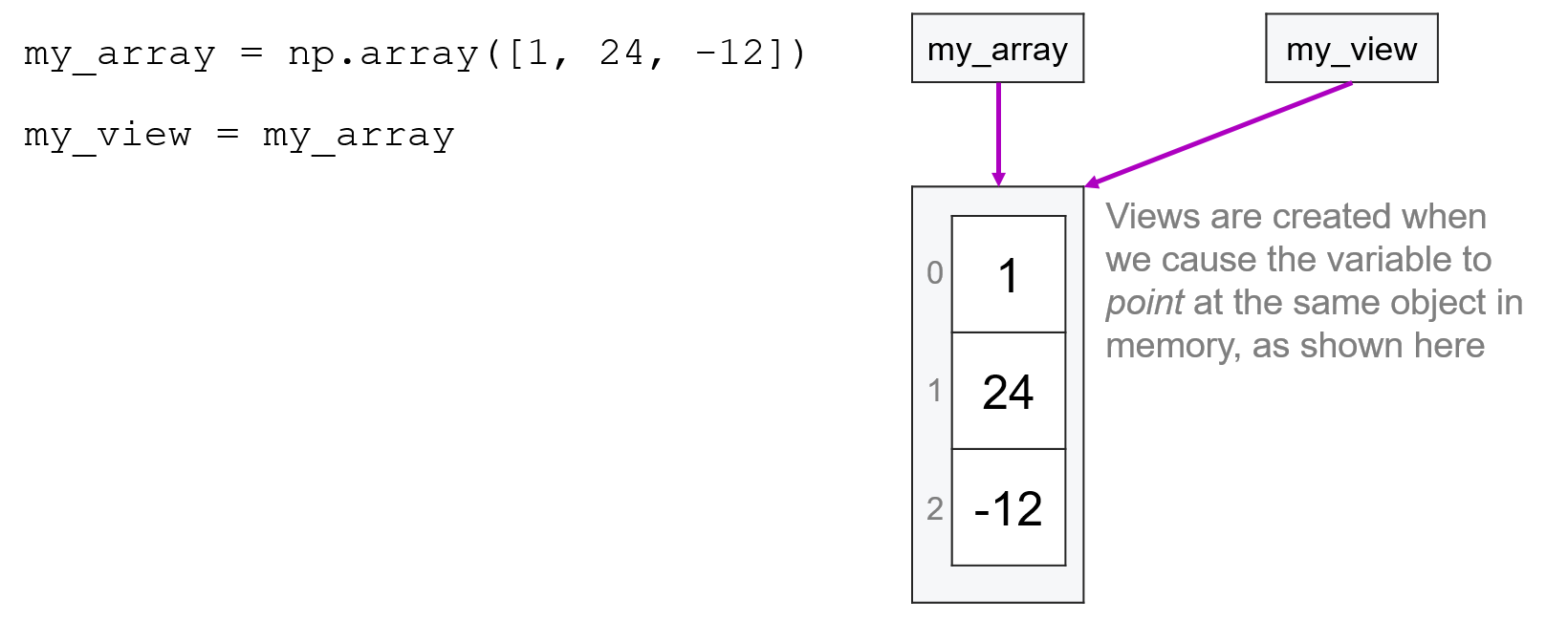

With this notation, let’s briefly review views and copies to present this concept using that notation. When we assign one variable the value of another variable, we are often simply assigning the pointer (or reference) of an object to the variable, as shown in the figure below, where we assign the pointer to the array object from my_array to my_view creating a view instead of a copy.

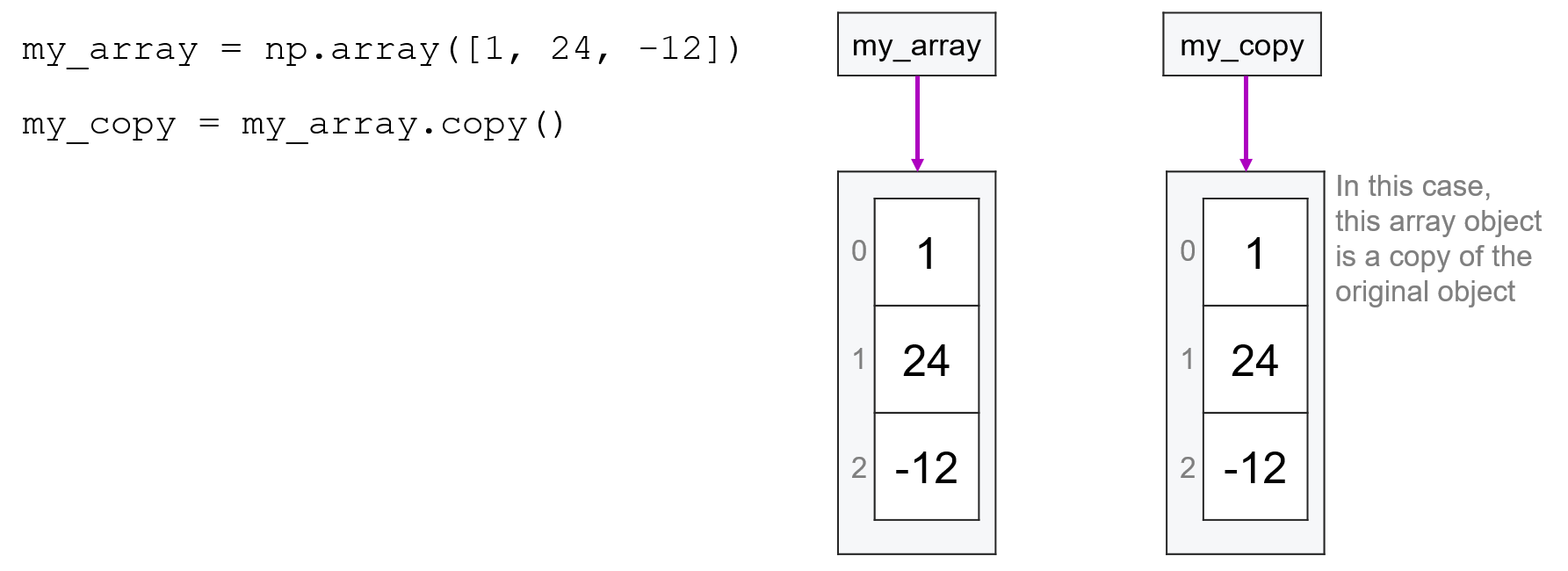

When we create a copy of an array, a new array object is created. The variable assigned the array contains a pointer to the new object instead of the original object, as shown below:

Going forward, we won’t be including these downward arrows indicating the relationship between variables and the corresponding objects that contain the data, since we want to keep the notation as simple as possible. However, this relationship is implied throughout and should be kept in mind, especially as it relates to the dynamics of views and copies.

Memory#

You can see all of this directly within the code as well. You can retrieve the memory address that each variable points at using the id function:

import numpy as np

my_array = np.array([1,-12,42])

id(my_array)

2549970475168

This number won’t have much meaning to us on its own, but this is the value that points to the segment of memory where our data are stored.

We can show this by creating a view and noting it points to the same memory address:

my_view = my_array

id(my_view)

2549970475168

Now if we make a copy of the variable, my_array, on the other hand, it will point to a different place in memory than did our original variable:

my_copy = my_array.copy()

id(my_copy)

2549970476208

While a deep understanding of the connection from the language to the physical hardware, such as memory, is not required to be a successful programmer, it can help our understanding of what may sometimes appear to be unexpected behavior. The relationship between variables and memory objects is a concept that worth being aware of for its implications to creating views or copies and for successfully using those views or copies for successfully coding our ideas.