When Do I Get a View and When Do I Get a Copy?#

Because numpy will usually create views when you subset a vector, and changes to views will propagate to the vectors associated with other variables, it’s really important to keep track of when the object you’re working with is a copy.

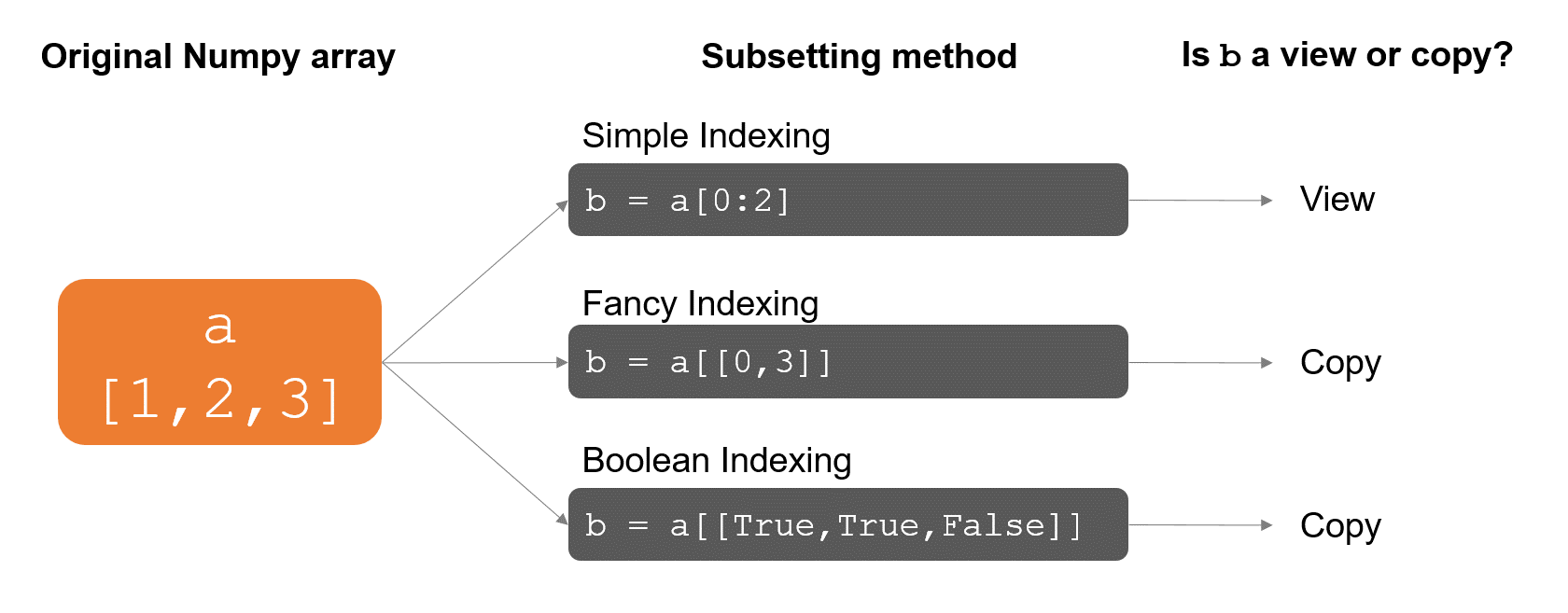

This brings us to the next slightly frustrating thing about numpy: the way that you ask for a subset will determine whether you get a view or a copy.

Views and Copies from Subsetting#

Generally speaking, numpy will give you a view if you use simple indexing to get a subset of an array, but it will provide a copy if you use any other methods. Recall that simple indexing is when you pass a single index, or a range of indices separated by a :. So my_vector[2] is simple indexing, and so is my_vector[2:4].

So, for example, this simple indexing returns a view:

import numpy as np

my_array = np.array([1, 2, 3])

my_subset = my_array[1:3]

my_subset

array([2, 3])

my_subset[0] = -1

my_array

array([ 1, -1, 3])

But if you ask for a subset any other way—such as with “fancy indexing” (where you pass a list when making your slice) or Boolean subsetting—you will NOT get a view, you will get a copy. As a result, changes made to your subset will not propagate back to my_array:

my_array = np.array([1, 2, 3])

my_subset = my_array[[1, 2]]

my_subset[0] = -1

my_array

array([1, 2, 3])

my_array = np.array([1, 2, 3])

my_slice = my_array[my_array >= 2]

my_slice[0] = -1

my_array

array([1, 2, 3])

This is summarized in the figure below:

Views and Copies When Editing#

We established above that numpy will only return a view when you subset with simple indexing, but not when you use fancy indexing or Boolean subsetting. But it’s also important to understand what types of modifications of a view will result in changes that propagate back to the original array.

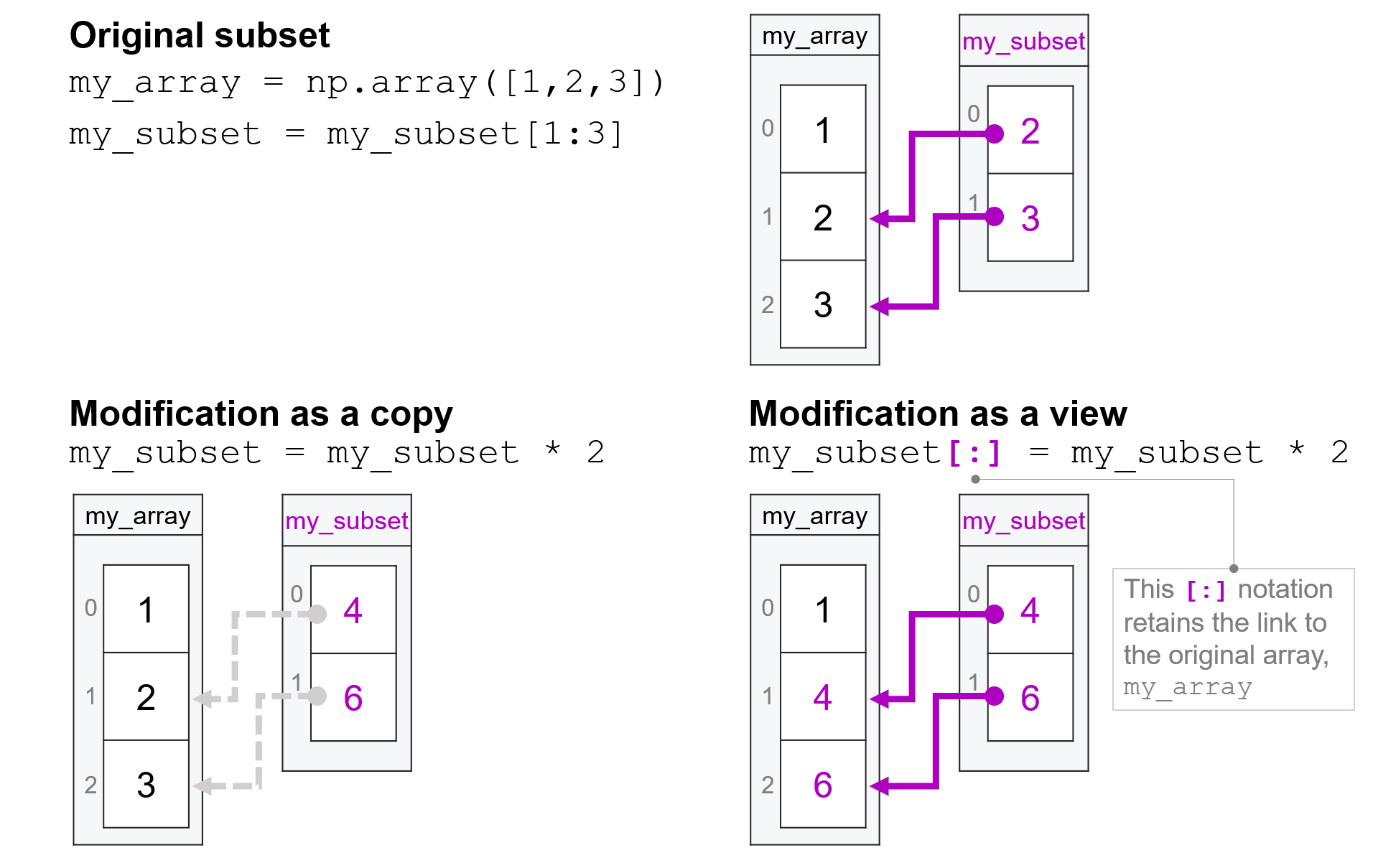

To illustrate consider the following code:

my_array = np.array([1, 2, 3])

my_subset = my_array[1:3]

my_subset = my_subset * 2

my_subset

array([4, 6])

We know that because it only used simple indexing, the command my_array[1:3] returned a view, and so my_subset begins its life as a view, sharing data with my_array.

But is that still true after we run the code my_subset = my_subset * 2?

The answer is no. That’s because when Python runs the code on the right side of the assignment operator (my_subset * 2) it generates a new array. Then, when it evaluates the assignment operation (my_subset =), it interprets that as a request to reassign the variable my_subset to point at that new array. As a result, by the end of this code, my_subset is no longer a view because the variable my_subset is now associated with a new array.

As a result, while the values associated with my_subset are 2 times the values that had been there previously, that doubling is not propagating back to my_array:

my_array

array([1, 2, 3])

So what would we do if we wanted to keep my_subset a view, and we wanted the doubling of the values in that view to propagate back to my_array?

In that case, we have to make clear to Python that we aren’t trying to reassign the variable my_subset to a new array, but instead, we are trying to insert the new values created by my_subset * 2 into the original array (the view) associated with my_subset. And we do that by putting [:] on the left-hand side of the assignment operator:

my_array = np.array([1, 2, 3])

my_subset = my_array[1:3]

my_subset[:] = my_subset * 2

my_subset

array([4, 6])

my_array

array([1, 4, 6])

Recall from our reading on modifying subsets of vectors that when Python sees an index on the left side of the assignment operator, it interprets that as saying “I’m not trying to reassign the variable my_subset, I’m trying to insert these values into the exposed entries of the array associated with my_subset.” And if we use my_subset[:], then we’re exposing all the entries in my_subset to have new values inserted.

If you have a lot of experience with object-oriented programming (don’t worry if you don’t), then one way to think about this is that using [] on the left side of the assignment operator is a lot like assigning a value to a property of an object. Just as my_object.my_property = "hello" modifies the property my_property associated with the object my_object but doesn’t reassign the variable my_object to the string "hello", so too does my_subset[:] = my_subset * 2 modify the underlying array associated with my_subset rather than re-assigning it to a new array.

Making a Copy#

Of course, this type of propagating behavior is not always desirable, and so if one wishes to pull a subset of a vector (or array) that is a full copy and not a view, one can just use the .copy() method:

my_vector = np.array([1, 2, 3, 4])

my_subset = my_vector[1:3].copy()

my_subset

array([2, 3])

my_subset[0] = -99

my_subset

array([-99, 3])

my_vector

array([1, 2, 3, 4])

How Much Faster Are Views?#

As previously noted, the reason that numpy uses views is because of the speed. But how much speed are we talking about?

Let’s create a little example to find out.

Suppose you work for an electric car company and are interested in understanding whether the performance of your energy recovery system declines after the car has been running for a while. To test this, you pull data on how efficiently the energy recovery system has been operating that’s been collected every couple of milliseconds over a long drive:

# Generate 1 million observations of

# fake efficiency data

efficiency_data = np.random.normal(100, 50, 1_000_000)

Now to see whether efficiency is changing over time, suppose that we want to measure average efficiency for the first third of our data and compare it to average efficiency for the last third of our data. We could do this with code that looks something like this:

degredation_over_time = np.mean(efficiency_data[700_000:1_000_001]) - np.mean(

efficiency_data[0:300_000]

)

But notice that nested in this are two subsets of our data—one that subsets the first 300,000 observations, and one that subsets the last 300,000 observations. These are precisely the type of operations for which numpy doesn’t want to spend time creating a full copy of those data, since we never actually want a new copy for future manipulations!

So let’s see how much faster those subsets are using views as opposed to copies:

import time

start = time.time()

# Let's do the subset 10,000 times and divide

# the overall time taken by 100

# so any small fluctuations in speed average out

# First with simple indexing to get views

for i in range(10_000):

initial_data = efficiency_data[0:300_000]

final_data = efficiency_data[700_000:1_000_001]

stop = time.time()

duration_with_views = (stop - start) / 10_000

print(f"Subsets with views took {duration_with_views * 1_000:.4f} milliseconds")

Subsets with views took 0.0002 milliseconds

# Fancy indexing *includes* the last endpoint

# so shifted down by 1 from simple indexing

first_subset = np.arange(0, 299_999)

second_subset = np.arange(700_000, 1_000_000)

start = time.time()

# Now do the subset using fancy indexing

# to ensure that we get copies

for i in range(10_000):

initial_data = efficiency_data[first_subset]

final_data = efficiency_data[second_subset]

stop = time.time()

duration_with_copies = (stop - start) / 10_000

print(f"Subsets with copies took {duration_with_copies * 1_000:.4f} milliseconds")

Subsets with copies took 0.6707 milliseconds

print(

f"Subsets with copies took {duration_with_copies / duration_with_views:,.0f} "

"times as long as with views"

)

Subsets with copies took 3,273 times as long as with views

So that’s why, despite being kinda a pain, numpy does this views / copies trick: because the speed up is more than 1,000x.

Now, does that mean that you should never use .copy() or fancy indexing? Let’s not get ahead of ourselves—even on my several-year-old on my Intel-based Macbook Pro, creating those subsets with fancy indexing (and thus using copies) may have been a lot slower than with simple indexing, but even with a vector with one million entries, each subset still took less than a millisecond.

Personally, I don’t think I’ve ever had occasion to worry about whether numpy is going to slowly because something I’m doing is generating copies, and honestly I’m much more worried about corrupting my data accidentally at some point because I’m working with a view instead of a copy than I am this performance penalty. So if I’m ever uncertain about whether I should use a view or a copy in a given circumstance, I will almost always just throw in a .copy().

But I do probably benefit from the fact that views are being used behind the scenes in the high performance libraries I use—like when I use a numpy library functions like np.sum(), or statistical modeling functions in machine learning libraries. And some of you students may very well end up doing high-performance work (say, climate modeling, or high-frequency trading) where this type of performance difference does matter, and so that’s why it’s there!